But our favorite dinosaurs in all their toothy, spiked, horned, and clawed glory will vanish in the blink of an eye, leaving behind scraps of skin, feather, and bone that we’ll unearth eons later as the only clues to let us know that such fantastic reptiles ever existed.

A small flock of avian species will carry on their family’s banner, perched to begin a new chapter of the dinosaurian story that will unfold through tens of millions of years to our modern era. We know the birds survive, and even thrive, in the aftermath of what’s to come.

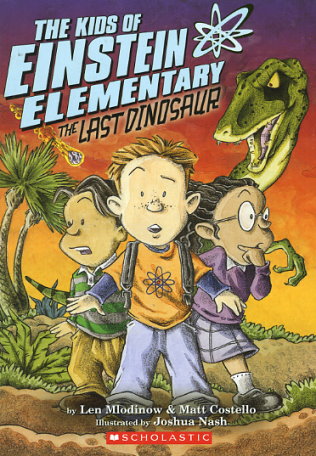

After more than 150 million years of shaping the world’s ecosystems and diversifying into an unparalleled saurian menagerie, the terrible lizards will come within a feather’s breadth of total annihilation. Tyrannosaurus rex-the tyrant king-will be toppled from their throne, along with every other species of non-avian dinosaur no matter their size, diet, or disposition. Contorted carcasses, dappled with cracked skin, will soon dot the razed landscape. Carpets of vegetation will be reduced to ash. In a matter of hours, everything before us will be wiped away. This is where we’ll watch the Age of Dinosaurs come crashing to a fiery close. The avians seem to grin, their tiny insect-snatching teeth jutting from their beaks. At this time of the day, with the sun still high and temperatures above 80 degrees, there’s barely another dinosaur in sight-the only other “terrible lizards” plainly in view are a couple of birds perched on a gnarled branch peeking out from just inside the shadow of the forest. The massive herbivore snorts, making some unseen mammal chitter and scramble in alarm somewhere in the shaded depths of the woods. The dinosaur is a massive quadruped, seemingly a big, tough-skinned platform meant to support a massive head decorated with a shield-like frill jutting from the back of the skull, a long horn over each eye, a short nose horn, and a parrot-like beak great for snipping vegetation that is ground to messy pulp by the plant-eater’s cheek teeth. But a familiar face soon reminds you that this is a different time.Ī Triceratops horridus ambles along the edge of the forest, three-foot-long brow horns slightly swaying to and fro as the pudgy dinosaur shuffles its scaly, ten-ton bulk over the damp earth. Magnolias and dogwoods shoulder their way into stands of conifers, ferns, and other low-lying plants gently waving in the light breeze drifting over the open ground you now stand upon. If you didn’t know any better, you might think you were wading on the edge of a Gulf Coast swamp on a midsummer day. The ground is a bit mushy, a fetid muck saturated from recent rains that caused a nearby floodplain stream to overrun its banks. It’s a day like most any other, a sunny afternoon in the Hell Creek of ancient Montana about 66 million years ago. Picture yourself in the Cretaceous period.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)